With my board game Four Humours launching on Kickstarter tomorrow, I thought I’d share a little behind-the-scenes “designer diary” about my game design process.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

The prisoner’s dilemma is a classic game theory scenario involving two people faced with jail time. There are three potential outcomes:

a) One person snitches and gets out of jail time, the other gets a 3-year sentence.

b) Neither person snitches and they both do 1 year in jail.

c) Both people snitch on each other and they both get 2-year sentences.

As a thought experiment, it’s fascinating to see whether people will choose to collaborate or betray. But how do you make this into a fun and meaningful board game?

In this post, I’ll dive into the development of my game Four Humours, in which I stumbled into a fun implementation of the prisoner’s dilemma that works for 2-6 players.

Four Humours

Five years ago, I was struck by the idea to make a game based on the four humours theory of personality. Originating with the Ancient Greeks and beloved by medieval philosophers, this theory said that an imbalance of the fluids in your body would influence your personality:

- Too much yel

low bile makes you choleric (aggressive and ambitious).

low bile makes you choleric (aggressive and ambitious). - Too much blood makes you sanguine (friendly and creative).

- Too much black bile makes you melancholic (introverted and perfectionistic).

- Too much phlegm makes you phlegmatic (patient and lazy).

I tried and mostly failed at six completely different games based on the four humours. But something about this weird theme possessed me to keep going. The armchair psychologist in me kept coming back to the idea of six character archetypes using combos of the humours:

- Nun (phlegmatic/melancholic)

- Peasant (phlegmatic/sanguine)

- Bard (sanguine/melancholic)

- Sorcerer (choleric/melancholic)

- Noble (choleric/sanguine)

- Knight (phlegmatic/choleric)

I always wanted to make a worker placement game where you place cubes on workers drawn into the scene itself, rather than placing generic meeples. When this worker scene idea came together with the dual characters, the bolt of lightning hit, and I came up with a “secret worker placement” mechanic.

Secret Worker Placement

Secret Worker Placement

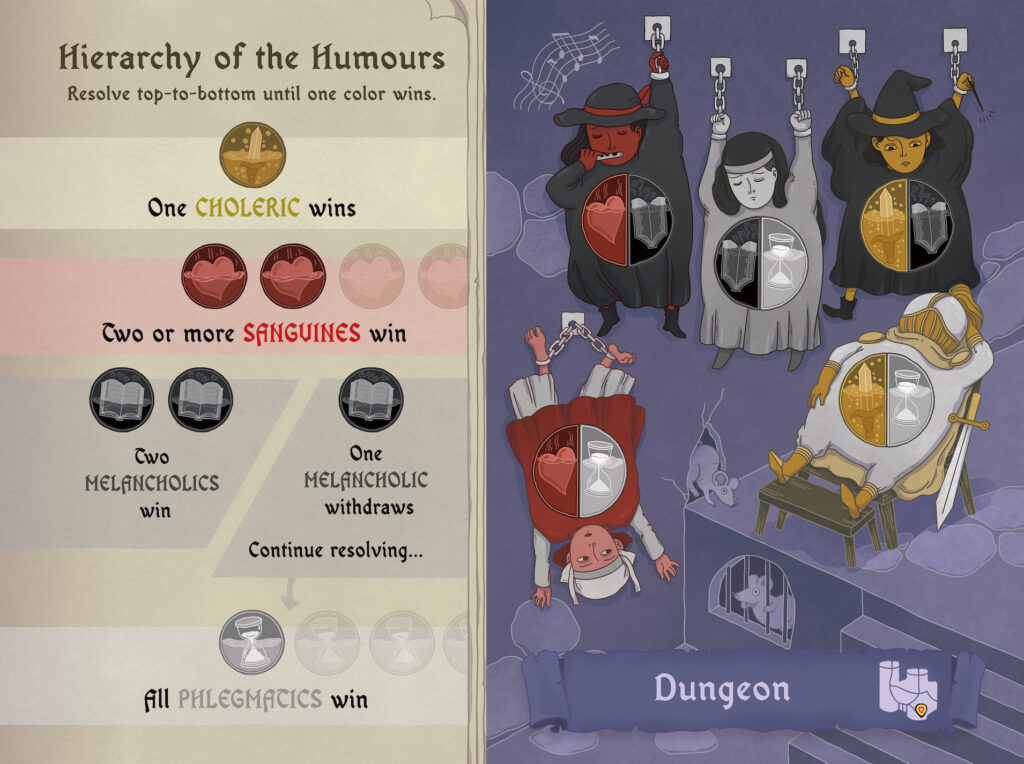

In my final iteration of Four Humours, you only do one thing on your turn: place a humour token facedown on a character, matching one of their two colors. Your goal is to win the location cards by cooperating with or backstabbing other players. When the secret tokens are revealed, the “hierarchy of the humours” determines if you were in it for yourself (choleric), you needed a friend (sanguine), you decided to be tricky (melancholic), or you waited patiently in hopes that one else wins (phlegmatic).

What Makes the Prisoner’s Dilemma Fun?

What Makes the Prisoner’s Dilemma Fun?

The core fun in the prisoner’s dilemma is guessing whether your opponent will work with you or not. In Four Humours, the next level of fun comes from deducing what your opponent played based on the dual characters – you have at least half the information of what they played (choleric or phlegmatic on a knight, for example), but you can deduce more based on when they played and what other tokens have been played on the card.

The prisoner’s dilemma idea is present on all the cards, but each one is a slightly different social puzzle. In addition, you’re deciding if you want to invest multiple tokens to insure a victory on one card, or split up your tokens onto multiple cards. The tension arises from a dynamic end to the round – when two cards fill, you resolve all four cards.

When I created the game, I assumed it needed 3 or more players to work. Why would you work with your opponent if it’s a zero-sum game? But my publisher, Adam’s Apple Games, said let’s try it at 2 players, and we soon realized it was like a chess match, deciding where to spend your tokens and how best to get them to work together. A happy accident!

Minimum Viable Mechanics

Through many iterations of Four Humours, the main thing I learned was to break down the game into only the mechanics that support the theme. To convey the four humours theme, my breakthrough came when I realized I could make four simple game rules based on the personality types themselves. The rest of the game could be a totally abstract area control game, but the humour hierarchy rules are what give it the thematic flavor, along with the art…

Art Signaling Gameplay

My publisher Adam was great about giving me creative control over the look of the game – I became art director and worked with our gifted illustrator Shirley Gong. My main direction was Monty Python meets Where’s Waldo. I loved the idea that each card’s art could give you a clue as to how the card might play out.

In the Watchtower, all of the knights could get along as phlegmatics, but you really have to watch your back with the choleric potential.

In the Laboratory, it’s hard to win as a peasant when you’re being experimented on by two powerful sorcerers.

In Lover’s Glen, a sanguine heart is clearly the best play, if you can convince your opponents to work with you.

Four Humours has been in the works for a long time, but that’s the way it goes with game design! Hundreds of pages of scribbled ideas and countless prototypes later, Four Humours made it to 3rd place in the 2019 Cardboard Edison Award, and it kept improving as I worked with my publisher Adam’s Apple Games. If you’re interested, check out the Kickstarter. You can also try it on Tabletop Simulator.